How do you engage huge numbers of people in clean energy? How do you overcome the negative press that renewables are up against? And how do create an energy-based project that’s genuinely particpatory and has broader social benefits?

How do you engage huge numbers of people in clean energy? How do you overcome the negative press that renewables are up against? And how do create an energy-based project that’s genuinely particpatory and has broader social benefits?

Those are some of the questions my colleagues and I at 10:10 were asking ourselves last year when we decided we’d like to launch some kind of project on renewables.

A year later and the project we came up with – Solar Schools – has just launched its pilot phase. It’s an exciting scheme, so I thought I’d post a few notes about it and the thinking behind it.

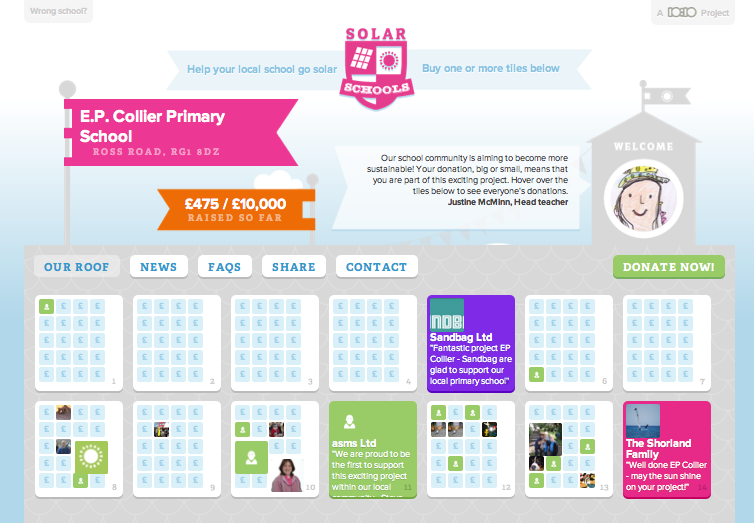

First, a quick summary. The aim of the project is to enable schools to fundraise the cost of a solar system from a wide number of people in their local communities. It works through a combination of a clever website and a set of related vouchers and other printed materials. The website provides each school with an “empty” solar roof diagram, which gradually fills up with a mosaic of local faces as community members buy vouchers or donate online.

The idea was inspired by Million Dollar Homepage, which became an internet phenomenon in 2005 when a student successfully sold $1m of adverts on his website, one pixel at a time. I liked the idea of using a similar visual approach for crowd-funding renewables – and solar was the obvious technology, being so flat and modular (think solar cells instead of pixels).

The idea was inspired by Million Dollar Homepage, which became an internet phenomenon in 2005 when a student successfully sold $1m of adverts on his website, one pixel at a time. I liked the idea of using a similar visual approach for crowd-funding renewables – and solar was the obvious technology, being so flat and modular (think solar cells instead of pixels).

At 10:10 we’d been thinking of doing something on renewables for a while, but we wanted to make sure it whatever we did was participatory (like all 10:10 activity) and had something new and interesting about it, to give it a chance of catching on widely. In the end, we put together the pixel-by-pixel solar concept with the idea that schools could be an ideal channel for creating mass engagement at a community level.

Other organisations have done good work on community energy schemes based on investments and returns, but we were keen to do something with donations. This way it might be practical to engage a much wider set of people. Better to get 500,000 people taking their first positive step with clean energy by donating £5 each, we figured, than to get 500 people who already care about climate and energy issues investing £5000 each.

The idea got exciting when we totted up the numbers. Let’s say 1000 schools took part, each with an average of 500 pupils. That’s 500,000 pupils, each of whom has close links to lots of other people such as parents, neighbours, grandparents, family friends and local businesses. Ten connections per pupil would make five million people – and that’s before you add on all the teachers, governors, PTA members and so on.

Getting all those people to visit a website would be difficult, so we came up with a way to connect the offline with the online – which I think is one of the most interesting things about the project. We provide the schools with perforated voucher books that look a bit like chequebooks. Kids sell the vouchers and record the details of the buyer on the stubs. Later, the school associates the name and email address with a little solar “tile” on the website, and the buyer then gets an automatic email inviting them to check out their tile and add a picture (using Facebook if they like) and a message of support.

To test the idea, we’ve signed up ten schools (many of them in Reading, but with others in the Scilly Isles, Norwich and elsewhere) for a pilot project. The first schools have just kicked off their fundraising, with targets ranging from £5000 to £50,000, and the first donations are starting to trickle in.

So why did we choose solar? And what about the case made by people like George Monbiot that it’s a virtually useless technology for the UK?

We picked solar partly because it was modular and ideally suited to the website idea, and partly because it’s the renewable energy option most easily available to the largest number of schools. As for the question of expense, as I plan to write about in a future post, the figures usually bandied about are somewhat misleading, not just because they ignore the fact that the power is being delivered directly to the consumer (especially in the case of schools, who use all their energy in the daytime) but also because they don’t consider the fact that when solar goes onto a building the inhabitants tend to slash their power use thanks to increasing energy literacy (well, that’s what all the anecdotal evidence suggests, even though no-one has studied it properly as far as I can tell).

Anyhow, in many ways the question of cost isn’t so relevant for this project, for three reasons. First, because any state subsidy via the feed-in tariffs is only going back to schools – i.e. bak to the state. Second, because the project is only partly about producing clean energy. It’s mainly about trying to get millions of kids and community members to take an interest in clean energy – and to feel empowered about getting involved. Third, we picked the project partly because the toolkit could be easily re-used in other countries – including those where the solar irradience is higher.

Only time will tell if the pilot will be successful, but after months of preparation it’s great to see the website up and running. Do check it out and make a donation. Even better, feel free to send feedback on the experience to help us make it better.

Finally, a few credits. Although I’ve been involved throughout on the conceptual side, the scheme was principally driven forward by the world’s best project manager, Daniel Vockins, supported by brilliant coordination from Amy Cameron, inspired design by Tom Flannery and incredibly fast web development from Simon Whitaker. It’s amazing how much such a small team achieved in just a few months.